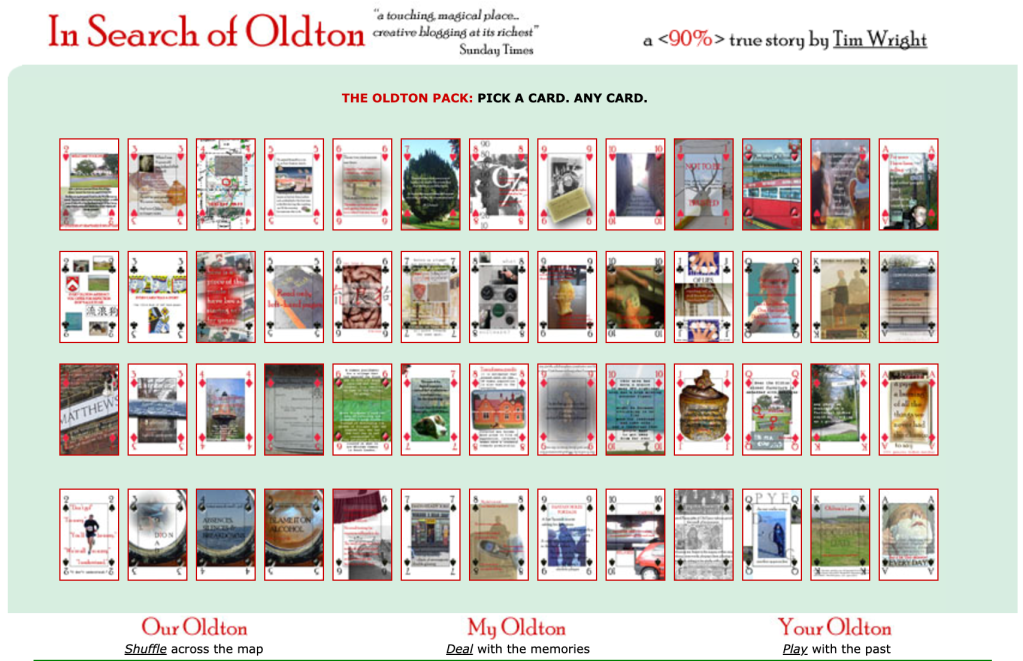

I’m delighted to say I have managed to update the In Search of Oldton website.

It has gradually been degrading over the past 20 years – broken links, defunct references, obsolete file formats, disappearing blog platforms etc – to the point that I wasn’t sure it was worth paying the hosting charges to keep it online.

In the end I decided it was worth saving, so I’ve transferred all the user contributions to a WordPress site from Typepad (finally I am free of Typepad!) and wherever needed I’ve updated pages and links.

I’ve also found a link to the audio drama that I wrote for BBC Radio 4 based on the website. You can find it on the Internet Archive here: https://archive.org/details/tim-wright-in-search-of-oldton

Coincidentally, I was contacted by the BFI not so long ago about the possibility of archiving another historical digital work I helped to make – Online Caroline.

This happens every few years, I have to say. Some hopeful junior researcher – at the British Library or the BFI or The Arts Council or a university – gets the idea that Online Caroline was a seminal online work of the early entertainment web that must be preserved and calls me up to request I send over a set of files he/she/they can pop onto their server.

Every time I have to explain how Online Caroline relies on a set of obsolete software tools, outmoded middleware (ColdFusion anyone?) and a highly bespoke database server setup based on ancient Microsoft applications and OS. Even the more obvious elements of the webcam footage and the character emails are not held as fixed assets – the webcam footage is assembled from a library of significant stills, the emails are personalised based on user data and behaviours.

It just isn’t an easy project to archive or recreate on a modern web setup.

After two or three email exchanges, the researchers usually give up, writing off Caroline (and me) as too difficult to deal with.

But they do usually sign off by asking if I might be able to supply a video walkthrough of the website. The answer is again not what they want to hear.

We probably should have made a video, but to be honest we weren’t thinking much about online video in 1998/99, and video cameras weren’t cheap. All we have left now is a very basic canned demo with none of the emails – which you can find at onlinecaroline.com.

If you want a sense about how the original production worked you could do worse than read Jill Walker’s essay: https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/how-i-was-played-by-online-caroline/

What this has all brought home to me is that I shouldn’t expect much of my work to survive. Writers of books have the luxury of knowing that a library somewhere will probably continue to preserve their works in pretty much the same form they were first published. Filmmakers have such institutions as the BFI to help preserve their work.

But it simply isn’t a possibility to preserve a lot of online work dating from the 1990s and early 2000s in anything like its original form.

Yes, I have managed to save some of the elements of works here on my blog – such as The Telectrocope (2008) and Kidmapped (2009). But very little of Such Tweet Sorrow (2010) survives, nothing of Mount Kristos (2001) or Planet Jemma (2003). And I’m currently in a wrangle with Soundcloud to rescue The Riddle of the Sands Adventure Club podcast files (2015) from oblivion.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not complaining. There’s something interesting about the idea of one’s work fading away in front of one’s eyes. And it’s perhaps part of the fun of immersing oneself in digital culture that things can so rapidly be replaced, deleted, remixed, overwritten .

There are days when I wish we’d planned a bit better for posterity (usually after yet another conversation with yet another researcher). But really we were having too much fun dreaming up new stuff and developing new ways of telling stories to be worried about what future generations would think of us.

Leave a comment