Like most other people I came away from Matt Locke’s #thestory2011 with my head bent. It’s taken a few days for me to recover. Now that I’ve calmed down, I’ve been left with two overarching themes rumbling around in my mind.

One is the thread of death, destruction and killing that wove its way through the day’s talks (self-immolating monks, exploding sheds, flesh-eating zombies), and with it came the accompanying methods we adopt to stave off death by ‘immortalising’ ourselves (as a txtbot, as a recorded ‘voice’, as a set of photo portraits, as sets of ‘audited’ data).

The other theme was provoked initially, I guess, by Adam Curtis’s contentious argument that the Internet may not be a particularly effective environment for telling stories, since – if I’m getting this right – most storytellers on the ‘Net (by which I think Curtis means the web) are rather naive or wilfully ignorant about the structures of power and commerce that surround and control the Net, and most Net/web writers are affected too much by the widespread Western fetishism for honouring personal emotion above all, so that we all often fail to offer anything more substantial than narrative ‘whimsy’ (the stories always explore ‘how do I feel about this?’ as opposed to ‘what do we think?’ ‘what should we do?’, or even simply ‘this is what *this* is’).

Whilst I found Curtis’s argument rather patronising and under-researched, it did make me wonder about the tools we choose to use to tell stories. For Karl James who came next onto the stage, the answer might be that we need only our voices and someone to listen to us (“*really* listen to us,” warns James). And then along came Cornelia Parker with images of Dickens’s quill, the Brontes’ nibs, Einstein’s chalk marks.

Why on earth have we bothered, I wonder, to progress from here: a quill, some ink and a sheet of paper; chalks and a board; a speaker and a listener?

To some extent, you see, Curtis is right to worry about what people like me are up to trying to use the web to tell stories. Many of the other speakers at the Story, it seemed to me, did indeed spend a lot of time being interested in deliberately using the wrong tools for the job: the Ministry of Stories using a retail space to ‘sell’ the idea of reading and writing; Phil Gyford attempting to boil down Pepys Diary entries into elegant tweets; Nick Ryan trying to define landscapes with the lights turned off; Mary Hamilton reducing narrative to ‘froth’ within a zombie LARP; Lucy Kimbell attempting to audit her life and publish it in the style of a company prospectus; Martin Parr getting studio photographers from around the world to make weird and wonderful portraits that he could have made himself; Graham Linehan finding the web to be both an inspiration and a distraction – and a sometimes trickisome way of collaborating with other writers; Cory Doctorow going the long way round to a method for re-inventing books.

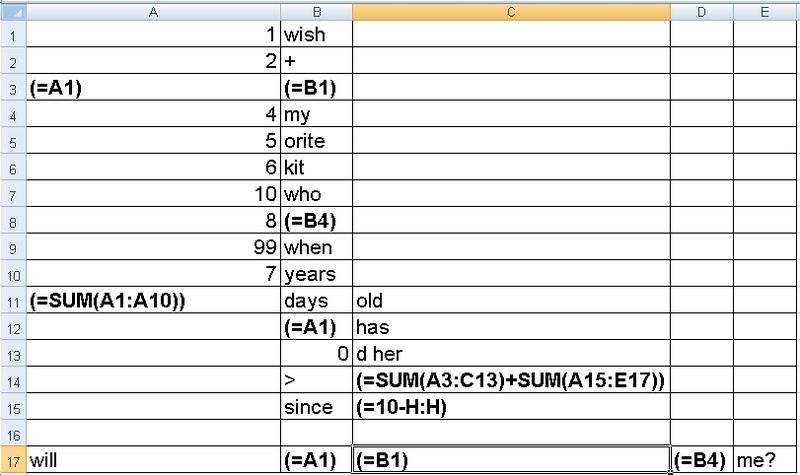

Don’t get me wrong. I found all these talks inspiring and thought-provoking. These people are all very VERY brainy. And I’m also of that party that seems to enjoy the wrong way of going about things, loves using tools that weren’t really designed to be used that way, deliberately wants to hi-jack business tools and processes for artistic purposes (notably the PC itself, a corporate/capitalist tool if ever there was one). I am a man after all who once attempted to write a poem in Excel:

It was odd, though, that the strongest desire I came away with from The Story was the desire to write with a quill – a quill perhaps that I had made myself.

I’m not saying I’m about to abandon my computer or this blog account, or quit Twitter. But certainly The Story made me think about trying to use much simpler forms of storytelling, using natural tools designed by artists for artists. And it leaves me asking these questions – for a digital writer, what are those natural tools designed by artists for artists? Where is the electronic equivalent of the quill? And who’s going to make me some internet chalks?

Leave a comment